Google's Education AI Finds Its Biggest Test in India's Classrooms

By admin | Jan 29, 2026 | 5 min read

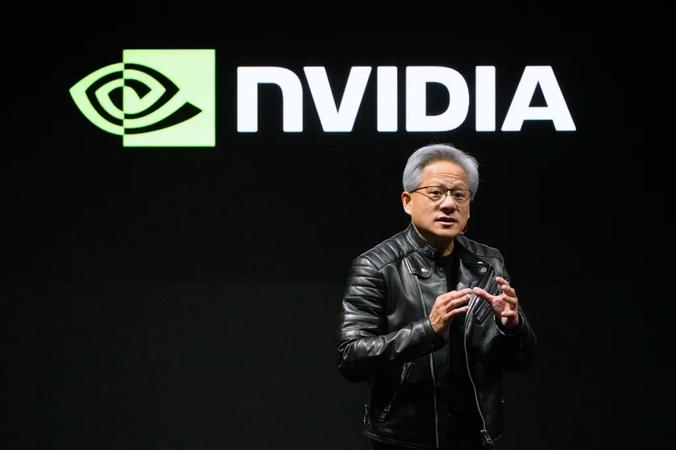

As artificial intelligence rapidly enters classrooms around the world, Google is discovering that the most critical lessons on scaling this technology are coming not from Silicon Valley, but from schools in India. The country has emerged as a primary testing ground for Google's educational AI, especially as competition heats up with rivals like OpenAI and Microsoft.

India now represents the largest global user base for Gemini in learning contexts, according to Chris Phillips, Google’s vice president and general manager for education. This adoption is happening within an educational landscape defined by state-level curricula, significant government involvement, and varied access to devices and internet connectivity. Phillips shared these insights during Google’s AI for Learning Forum in New Delhi this week, where he engaged with school administrators and officials to understand how AI tools are being implemented.

The immense scale of India’s education system underscores its importance as a testing environment. Official reports indicate the school system serves approximately 247 million students across nearly 1.47 million schools, supported by over 10 million teachers. Higher education is similarly vast, with enrollments exceeding 43 million students—a 26.5% increase since 2014—creating a complex, decentralized structure that poses unique challenges for rolling out AI tools.

A key lesson for Google has been that educational AI cannot be deployed as a one-size-fits-all product. In India, where states control curricula and ministries are deeply involved, Google has had to design its AI so that schools and administrators dictate how and where it is used. This represents a shift from the company’s traditional approach of building globally scalable products without tailoring to individual institutions.

This diversity is also influencing Google’s vision for AI-driven learning. Adoption of multimodal learning—which combines video, audio, and images with text—is progressing faster in India. This approach addresses the need to reach students with different languages, learning styles, and levels of access, particularly in classrooms that are not centered on text-heavy instruction.

Google has also pivoted to design its educational AI around teachers as the primary users, rather than students. The focus is on tools that assist educators with planning, assessment, and classroom management, not on creating AI experiences that bypass them. Phillips emphasized that preserving the teacher-student relationship is essential, stating the goal is to support that dynamic, not replace it.

In many Indian classrooms, AI is being introduced in settings without reliable internet or one device per student. Google is working in environments where devices are shared, connectivity is unstable, or learning transitions directly from pen and paper to AI tools. This variability makes access a universal priority, but one that must be adapted to local realities.

These early lessons from India are already shaping specific deployments. Initiatives include AI-powered preparation for the JEE Main exam via Gemini, a teacher training program reaching 40,000 educators in Kendriya Vidyalaya schools, and partnerships with government institutions on vocational and higher education, including India’s first AI-enabled state university.

For Google, India’s experience previews challenges that will likely arise globally as AI integrates further into public education. Questions of control, access, and localization—already prominent in India—are expected to increasingly influence how educational AI scales worldwide.

This focus on education reflects a broader shift in how generative AI is being used. While entertainment was the dominant application last year, learning has now become one of the most common uses, especially among younger people. As students turn to AI for studying and skill-building, education has become a more urgent and significant arena for Google.

India’s complex educational landscape is attracting rivals as well. OpenAI is building a local education team, having hired former Coursera executive Raghav Gupta to lead its efforts and launching a Learning Accelerator program. Microsoft, meanwhile, is expanding partnerships with Indian institutions and edtech companies like Physics Wallah to promote AI-based learning and teacher training, highlighting education as a key competitive battleground.

However, this push into classrooms coincides with growing concerns. India’s latest Economic Survey warns of risks from uncritical AI use, including over-reliance on automated tools and potential negative impacts on learning outcomes. Citing studies from MIT and Microsoft, the survey notes that dependence on AI for creative tasks can contribute to cognitive atrophy and weaken critical thinking—a reminder that the race to adopt AI must be balanced with caution about its effects on learning itself.

Whether Google’s India strategy becomes a model for other countries remains to be seen. Yet as generative AI advances deeper into public education systems worldwide, the pressures and lessons emerging from India are likely to resonate globally, making its experience increasingly relevant for the entire industry.

Comments

Please log in to leave a comment.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!